Tree Warriors

Tree Warriors

Tree Warriors, Known and Unknown

There are many around the world who give their lives planting trees; and many who have initiated large-scale planting programmes measured in millions of trees. There are also many around the world who continue to risk, even lose, their lives protecting trees – whether as individuals such as Chico Mendes, the assassinated leader of the rubber-tappers in Brazil, or as communities, tribes such as the Yanomami of Brazil or villagers like those of Gopeshwar in India, who placed their bodies between the axes and their trees, whose stance and actions gave rise to the Chipko or Hugging Movement.

But heroic acts do not need to be extreme or spectacular. We don’t have to be visionaries, the founders of movements or organisations, tree-warriors or missionaries. Heroic acts can be simple, though they may also need to be sustained. One of the most significant areas in which all of us can become heroically engaged is in personal changes in everyday lifestyle. While it is the rapacious hunger of industry and commerce which results in the large-scale destruction of primeval forests, this is simply to feed the demands of our lifestyles. Thus, “living simply so that others may simply live”, as Gandhi suggested, may be one of the most heroic acts in which we can all become engaged, individually and collectively.

Below, we pay tribute to a few of the many tree warriors whose acts and initiatives, while an inspiration to others, have had such a huge impact in worlds around them:

photo by Shaun Walker

Julia Butterfly Hill, USA

Her Struggle to Save

The Giant Redwoods of California

“These kings of the forest, the noblest of the race, rightly belong to the world, but as they are in California, we cannot escape the responsibility as their guardians,” wrote naturalist, John Muir. “Fortunately the American people are equal to this trust,” he affirmed hopefully. Unfortunately, it is the plunderers who appear to be ruling the day; and few are prepared to stand against them. This is the story of one of these few, a modern day heroine, who dared to confront the mighty and overwhelming odds.

Julia Butterfly Hill, a young poetess, lived in a giant redwood for more than two years, 738 days to be precise, on a two-by-three meter platform – risking her life, besieged by security guards, buzzed by a helicopter, suffering endless rain, cruel icewind storms and frostbite, suffocation and painful swellings from napalm, with days so bad “nothing but tears fell out of my eyes and heart” – to protest the destruction of an ancient forest being destroyed by loggers.

“I will continue to stand for what I believe in; and I will continue to refuse to back down and go away,” she affirmed defiantly:

“No person, no business, and no government has the right to destroy the gift of life. No one has the right to steal from the future in order to make a quick buck today. Enough is enough. It’s time we as humans return to living only off the Earth’s interest instead of drawing from its capital. And it’s time we restored some of the capital investment that we’ve already stolen.”

She came down only when the lumber company agreed to preserve the tree in which she lived, nicknamed Luna – “the best friend I ever had.”

Butterfly Hill, may she long serve as an inspiration to others. “Yes, one person can make a difference,” she proclaimed triumphantly. “Each one of us does.”

Her story is recorded in The Legacy of Luna, published by Harper SanFrancisco.

Postscript: “A grove of Redwoods and Sequoias should be maintained in the same way as a great and beautiful cathedral,” said President Theodore Roosevelt reverently – unlike Ronald Reagan, who declared outrageously, “If you’ve seen one Redwood, you’ve see them all.”

If we don’t like our leaders, we are free to change them. Note the words of Robert Redford: “The most important step we can take is to tell our leaders that if they don’t protect the environment, they won’t get elected.”

see more: ![]() Julia's weblog

Julia's weblog

Julia's current project: ![]() Engage Network

Engage Network

Wangari Maathai, Kenya

Africa’s Forest Goddess & Nobel Laureate

photo by Martin Rowe

“A mad woman,” said Kenya’s former president, Daniel Moi, referring to Wangari Maathai, “a threat to the order and security of the country.”

How far from being the truth. More accurately she could then have been described as a woman of vision, whose inspired and daring acts have ever been for her nation’s saving.

Professor Wangari Maathai, who has degrees in biological sciences from universities in her native Kenya as well as from the USA, was brought up in the once lush uplands of Nyeri, near Mount Kenya.

A Nobel Peace Prize for planting trees? When Wangari won it in 2004, she became the first African woman to receive a Nobel Prize. When it was announced, her name was relatively unknown outside Africa; but for almost thirty years she had been causing a stir not only in her own country but elsewhere on the continent, confronting businessmen, politicians and governments.

In 1977, she planted seven trees in a Nairobi park. The same year, she brought together a closely knit group consisting mainly of village women and melded them into an organization which became known as the Green Belt Movement. Its aim was the reforesting of land which, among other benefits, would provide fuel for the poor and bring a halt to extensive soil erosion. The idea had come to her a couple of years earlier, when she was in the middle of battling university authorities over wage discrimination against female staff. At the same time, at a gathering, she heard women from rural areas telling how their land was being devastated. They had no income, no water, no firewood, they complained. It was then that the equation between trees and the well-being of these women dawned on her. “Trees,” she has written, “would provide a supply of wood that would enable women to cook nutritious foods, wood for fencing, shade for humans and goats, protect watersheds and bind soil and heal the land by bringing back birds and small animals.”

The first time she came to the notice of officialdom was when she walked into the forestry ministry in the capital and demanded 15 million seedlings, which she got.

The Green Belt Movement urged, inspired and assisted communities in planting trees everywhere, with the result that over 30 million trees have been planted on school grounds, roadsides and open spaces, in Kenya as well as elsewhere in Africa. In Kenya alone, there are more than 600 community networks; and branches in 20 other countries. People are now harvesting the fuel and fruit from these trees; and springs have returned, which had once dried up.

In addition to planting trees and bringing a halt to widespread forest clearances, the Movement grew rapidly into an organization working to preserve biodiversity, fight mindless developments, as well as to empower women generally while promoting their rights.

“Women,” she proclaimed in her Nobel speech, “will be Africa’s salvation … Women in Africa carry the burden of poverty and conflict. We’ve been waiting for Africa’s leaders, who are mostly men, to change. Women have a vital role in challenging the men to be responsible to us and to our children – to stop sending them off to die in their wars …”

She campaigned strenuously and ultimately dangerously against what were proclaimed as national developments:

“Developments undertaken by governments do great harm to the environment and do not improve our lives … Development which plunders human resources – forests, land, water, air and food – is short-sighted and self-eliminating. Yet for many leaders, development means extensive farming of cash crops, expensive dams, luxury hotels, airports, big hospitals, heavily armed armies and supermarkets. These are the priorities in national budgets. Never mind that they may not reflect the needs of the people who, if asked, would prefer basic needs like food, shelter, education, clean water, local clinics, information and freedom.”

In 1989, President Moi came up with the idea of building a mammoth skyscraper for Kenya’s ruling political party in a park in central Nairobi. Maathai led the public protest.

“We owe billions to foreign banks,” she said. “The people are starving. They need food, medicines and education. They do not need a skyscraper.”

The protest triumphed. But Maathai paid a high price for her blunt-speaking while taking on the political establishment. Faced with death threats, she fled to Tanzania with her children. On her return she was arrested and imprisoned; and, on one occasion, in

1992, was beaten unconscious by police during a hunger strike.

But her fortunes changed in 2002, when she was elected to parliament, as the Moi regime was defeated and Mwai Kibaki took over. She was immediately appointed deputy minister for the environment, natural resources and wildlife.

Resolved to halt all forest clearances, she went into action straight away, putting her newly-gained position on the line. “I would rather give up my seat than see our forest destroyed,” she stated, threatening to do so if forest clearances were not stopped.

Aside from winning a Nobel Peace Prize, she has been crowned informally with many titles, Africa’s Forest Goddess among them.

Truly, a great warrior.

see more: ![]() The Green Belt Movement

The Green Belt Movement

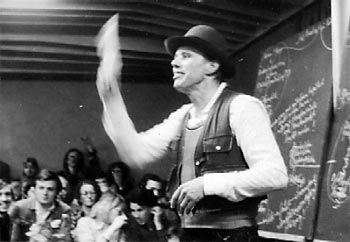

Joseph Beuys, lecturing in Achberg, Germany 1978

photo by Rainer Rappman

Joseph Beuys, Germany

7,000 Oaks in the Middle of a City

Joseph Beuys was a famous artist, but also a social and political one. Increasingly, he wanted to be outdoors, creating and interacting with nature and human beings in their work places. His 7000 Oaks Planting Project was a far-reaching visionary programme which transformed the sidewalks and landscape of Kassel in Germany. One summer, in 1982, he was asked to participate in the well-known international art event held in that city every few years, entitled Documenta. This was to be Documenta 7. He agreed; and eventually arrived with a fleet of trucks loaded with basalt rocks from a nearby quarry, which he dumped in the city centre.

From the air it could be seen that this pile had been arranged in the shape of a large arrow, at the tip of which Beuys had planted a single tree.

Beuys planting the fist of the 7000 oaks in front of the Fridericianum in Kassell, 1982.

photo © Dieter Schwerdtle Fotografiea

“This is my art! Nobody touch it,” he said.

Then, almost as an after-thought: “O.K. You can move a rock, but only if you plant a tree next to it.”

Thus it was that between 1982 and 1987, 7000 Oaks were planted, with a basalt rock set next to each tree.

This was the beginning of what he called “social sculpture,” describing the process of communication and collaboration that can take place between artists and citizens in creating environmental artworks beneficial to the community.

“I believe,” he said, “that planting these Oaks is necessary not only in biospheric terms, that is to say, in the context of matter and ecology, but in that it will raise ecological consciousness; raise it increasingly, in the course of years to come, because we shall never stop planting …

“This will be a regenerative activity; it will be a therapy for all of the problems we are standing before … I wished to go completely outside and to make a symbolic start for my enterprise of regenerating the life of humankind within the body of society and to prepare a positive future in this context … The tree is a symbol of regeneration … The Oak is especially so … It has always been a form of sculpture, a symbol for this planet …

Some of the 7,000 oaks and accompanying basalt rocks

photo by Slowart at en.wikipedia

“The planting of 7000 Oaks is thus only a symbolic beginning. And such a symbolic beginning requires a marker, in this case a basalt column. The intention of such a tree-planting event is to point up the transformation of all of life, of society, and of the whole ecological system. My point with these 7000 trees was that each would be a monument, consisting of a living part, the live tree, changing all the time, and a crystalline mass, maintaining its shape, size, and weight. This stone can be transformed only by taking from it, when a piece splinters off, say, never by growing. By placing these two objects side by side, the proportionality of the monument’s two parts will never be the same.

“So now we have six and seven-year-old Oaks, and the stone dominates them. In a few years’ time, stone and tree will be in balance; and in twenty years’ time we may see that gradually the stone has become an adjunct at the foot of the Oak or whatever tree it may be.”

The first tree to be planted, 20 years later

photo by Malte Ruhnke

![]()

Alan Watson, Scotland

Trees for Life:

Restoring the Caledonian Forest

Anyone can become a tree-warrior by responding to the needs and challenges in their own local environments. A good example of this is the response and life-time work of Alan Watson Featherstone who decided to engage in restoring the Caledonian Forest to a large area of the Highlands of his native Scotland. The Caledonian Forest once covered 1.5 million hectares, only 1% of which remains today. In 1985, to assist him in his endeavour, he founded Trees for Life, which has since engaged thousands of volunteer participants.

In response to the UN’s Billion Tree Campaign, Trees for Life pledged to plant 100,000 trees in 2007; and declared its long-term goal of planting 10 million trees by the end of 2010, a staggering 3044 trees every single day. Just as the journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step, great effects may be achieved by the steady day-to-day commitment to a single idea.

Alan has been a member of the Findhorn Community since 1978, where Trees for Life was founded. He is now spearheading another major project, Restoring the Earth, in which he is using his tried and tested methods to promote the restoration of the world’s degraded ecosystems. He sees this as the essential and central task for humanity in the 21st Century.

see more: ![]() Trees for Life

Trees for Life

and ![]() Restore the Earth

Restore the Earth

and ![]() Earth Restoration Service

Earth Restoration Service

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

The above extracts are from Gospel of the Living Tree: for Mystics, Lovers, Poets & Warriors by Roderic Knowles, published by (and available online from) Earth Cosmos Press